My Joe Cole Summer

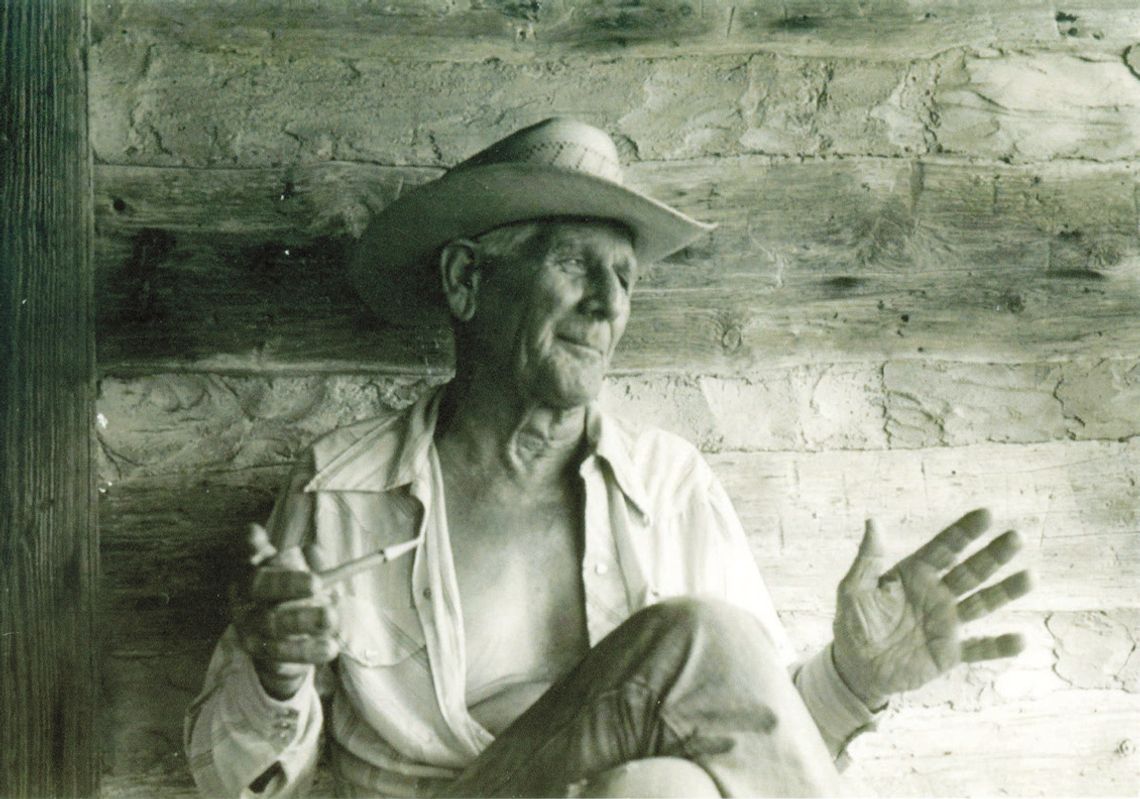

It was June of 1958, during an eagerly awaited summer break from school. We heard him long before we saw the truck bouncing unfamiliarly down our rutted gravel driveway— the faded, nearly rusted GMC pickup parked under the big cedar tree near our front porch. Out stepped a somewhat aged, weather-trimmed cowboy. From his steel gray Stetson hat to the starched long-sleeved white shirt and khakis tucked neatly into a “Sunday best” pair of cowboy boots. He stepped up, hat in hand, politely introduced himself; speaking to my mother, he asked. “Ma’am, I am doing some surveys of old cemeteries in this part of the county. Do you know where the Rabb Family Cemetery is located?”

My mother responded with a hesitant “No,” but she looked back at me in question. I raised my hand and shouted out, “Yes, Sir, I know exactly where it is.” Ten minutes later, my younger brothers and I were standing next to his pick-up, surveying copies of maps and deed documents. Here I was, a ten-year-old, barefoot and in shorts, sharing vital information with an adult.

After gaining permission, Mr. Cole, my brothers, and I were off down a narrow cow trail to find the William Rabb Family and Massadonia Hill Cemeteries. After several hours of counting graves, deciphering markers, measuring, taking compass readings and making detailed notes on what we had found, we took a cool break in the shade. The conversation led to other nearby cemeteries and landmarks on Mr. Cole’s list, some of which I knew and had visited. He asked, “What are you doing tomorrow?”

“Wow,” I thought. “I’m on the survey team. The adventure begins.” I made a mental note to wear shoes and long pants tomorrow.

The next day, Joe (Mr. Cole) and I visited two small family cemeteries and searched unsuccessfully for two others. We visited Indian Hill, Chalk Bluff, the Rabb Bridge, and the Old Stone Fort (where we jumped a fence). We drove the La Bahia Road and walked parts of the Gotcher Trace. My compensation for the day was a hamburger, fries, and an RC Cola at the Hobratschk Store on Indian Creek.

The next three days were spent exploring the distant reaches of Fayette and the borderlands of Bastrop and Lee Counties. Most locations were long abandoned cemeteries, while others were pioneer home sites, river crossings, Indian campgrounds and cattle dipping vats. He was drawn to the old iron truss bridges with wood planking; this trip was his first look at the (yet-to-benamed) “piano bridge” of Dubina. My daily compensation increased to BBQ and Little Debbie's. I also had the opportunity to meet three of his “running buddies,” who shared his passion for local history: Walter Freytag of La Grange, Clyde Reynolds of Bastrop and John Knox of Giddings.

My apprenticeship with the old cowboy (everybody is old to a ten-year-old) lasted only five days, but some of the lessons learned took root for a lifetime. As an adult, I would run into Joe Cole or a son occasionally at different events, but mostly, it was the stories I heard of a real-life cowboy living in a modern world. He passed on in 1999 at the age of ninety-seven—no doubt a full life lived on his terms. He was a treasure hunter, with the treasure not always measured in monetary value. As an avocational archeologist, I have learned that it is not what you find, but what you find out. Today, local libraries, archives, and museums safeguard Cole's field reports, his many cemetery surveys are detailed and accurate, and his hand-drawn maps are legendary. He was a horse trader, rock hunter, maker of rawhide furniture, and a collector of everything “yesterday.” Descended from early pioneer stock, he was an avid storyteller. Like all the other Texas storytellers, I will quote John Steinbeck, "Like most passionate nations, Texas has its own private history based on, but not limited by, facts.”

Cole’s wit and “colorful” language was only tempered by the solid values he held true. I think he would have hated social media.

Wild Joe Cole cattle-you can still hear that phrase tossed around Smithville today. Being the ultimate cowman, his rented pastures ranged far and wide. Many locations were isolated, visited once or twice a year for a round-up. His cattle grew wild and cantankerous.

My grandfather was a handshake partner with Joe on at least one venture. One Saturday, we were on my grandparents’ front porch; the horses were all loaded, and the stock trailers were ready to roll. The weekend, cowboys, my dad, and two uncles were checking their gear. I was the designated gate/gap opener. Grandfather was giving his last-minute briefing on the extraction (round-up). Just before leaving, he handed my dad his beloved Winchester Model 94, lever action. Seeing the confused look on my dad’s face he says, "These are Joe Cole Cattle. We can't catch all of ‘um.”

My wish is that in some far corner of Bastrop County, in the thickest thorn and underbrush, there roams a heard of Joe Cole Cattle, feral, some not having seen a human in their lifetime.